- Home

- Thomas C. Foster

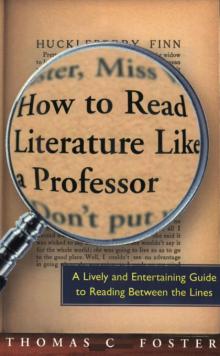

How to Read Literature Like a Professor

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Read online

How to Read

Literature

Like a

Professor

How to Read

Literature

Like a

Professor

A Lively and Entertaining Guide

to Reading Between the Lines

THOMAS C. FOSTER

Quill

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

For my sons, Robert and Nathan

Introduction – How’d He Do That?

p. xi MR. LINDNER? THAT MILQUETOAST?

Right. Mr. Lindner the milquetoast. So what did you think the devil would look like? If he were red with a tail, horns, and cloven hooves, any fool could say no.

The class and I are discussing Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (1959), one of the great plays of the American theater. The incredulous questions have come, as they often do, in response to my innocent suggestion that Mr. Lindner is the devil. The Youngers, an African American family in Chicago, have made a down payment on a house in an all-white neighborhood. Mr. Lindner, a meekly apologetic little man, has been dispatched from the neighborhood association, check in hand, to buy out the family’s claim on the house. At first, Walter Lee p. xii Younger, the protagonist, confidently turns down the offer, believing that the family’s money (in the form of a life insurance payment after his father’s recent death) is secure. Shortly afterward, however, he discovers that two-thirds of that money has been stolen. All of a sudden the previously insulting offer comes to look like his financial salvation.

Bargains with the devil go back a long way in Western culture. In all the versions of the Faust legend, which is the dominant form of this type of story, the hero is offered something he desperately wants—power or knowledge or a fastball that will beat the Yankees—and all he has to give up is his soul. This pattern holds from the Elizabethan Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus through the nineteenth-century Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust to the twentieth century’s Stephen Vincent Benét’s “The Devil and Daniel Webster” and Damn Yankees. In Hansberry’s version, when Mr. Lindner makes his offer, he doesn’t demand Walter Lee’s soul; in fact, he doesn’t even know that he’s demanding it. He is, though. Walter Lee can be rescued from the monetary crisis he has brought upon the family; all he has to do is admit that he’s not the equal of the white residents who don’t want him moving in, that his pride and self-respect, his identity, can be bought. If that’s not selling your soul, then what is it?

The chief difference between Hansberry’s version of the Faustian bargain and others is that Walter Lee ultimately resists the satanic temptation. Previous versions have been either tragic or comic depending on whether the devil successfully collects the soul at the end of the work. Here, the protagonist psychologically makes the deal but then looks at himself and at the true cost and recovers in time to reject the devil’s—Mr. Lindner’s—offer. The resulting play, for all its tears and anguish, is structurally comic—the tragic downfall threatened but avoided—and Walter Lee grows to heroic stature in p. xiii wrestling with his own demons as well as the external one, Lindner, and coming through without falling.

A moment occurs in this exchange between professor and student when each of us adopts a look. My look says, “What, you don’t get it?” Theirs says, “We don’t get it. And we think you’re making it up.” We’re having a communication problem. Basically, we’ve all read the same story, but we haven’t used the same analytical apparatus. If you’ve ever spent time in a literature classroom as a student or a professor, you know this moment. It may seem at times as if the professor is either inventing interpretations out of thin air or else performing parlor tricks, a sort of analytical sleight of hand.

Actually, neither of these is the case; rather, the professor, as the slightly more experienced reader, has acquired over the years the use of a certain “language of reading,” something to which the students are only beginning to be introduced. What I’m talking about is a grammar of literature, a set of conventions and patterns, codes and rules, that we learn to employ in dealing with a piece of writing. Every language has a grammar, a set of rules that govern usage and meaning, and literary language is no different. It’s all more or less arbitrary, of course, just like language itself. Take the word “arbitrary” as an example: it doesn’t mean anything inherently; rather, at some point in our past we agreed that it would mean what it does, and it does so only in English (those sounds would be so much gibberish in Japanese or Finnish). So too with art: we decided to agree that perspective—the set of tricks artists use to provide the illusion of depth—was a good thing and vital to painting. This occurred during the Renaissance in Europe, but when Western and Oriental art encountered each other in the p. xiv 1700s, Japanese artists and their audiences were serenely untroubled by the lack of perspective in their painting. No one felt it particularly essential to the experience of pictorial art.

Literature has its grammar, too. You knew that, of course. Even if you didn’t know that, you knew from the structure of the preceding paragraph that it was coming. How? The grammar of the essay. You can read, and part of reading is knowing the conventions, recognizing them, and anticipating the results. When someone introduces a topic (the grammar of literature), then digresses to show other topics (language, art, music, dog training—it doesn’t matter what examples; as soon as you see a couple of them, you recognize the pattern), you know he’s coming back with an application of those examples to the main topic (voilà!). And he did. So now we’re all happy, because the convention has been used, observed, noted, anticipated, and fulfilled. What more can you want from a paragraph?

Well, as I was saying before I so rudely digressed, so too in literature. Stories and novels have a very large set of conventions: types of characters, plot rhythms, chapter structures, point-of-view limitations. Poems have a great many of their own, involving form, structure, rhythm, rhyme. Plays, too. And then there are conventions that cross genre lines. Spring is largely universal. So is snow. So is darkness. And sleep. When spring is mentioned in a story, a poem, or a play, a veritable constellation of associations rises in our imaginative sky: youth, promise, new life, young lambs, children skipping . . . on and on. And if we associate even further, that constellation may lead us to more abstract concepts such as rebirth, fertility, renewal.

Okay, let’s say you’re right and there is a set of conventions, a key to reading literature. How do I get so I can recognize these?

Same way you get to Carnegie Hall. Practice.

When lay readers encounter a fictive text, they focus, as they should, on the story and the characters: who are these people, what are they doing, and what wonderful or terrible things are p. xv happening to them? Such readers respond first of all, and sometimes only, to their reading on an emotional level; the work affects them, producing joy or revulsion, laughter or tears, anxiety or elation. In other words, they are emotionally and instinctively involved in the work. This is the response level that virtually every writer who has ever set pen to paper or fingertip to keyboard has hoped for when sending the novel, along with a prayer, to the publisher. When an English professor reads, on the other hand, he will accept the affective response level of the story (we don’t mind a good cry when Little Nell dies), but a lot of his attention will be engaged by other elements of the novel. Where did that effect come from? Whom does this character resemble? Where have I seen this situation before? Didn’t Dante (or Chaucer, or Merle Haggard) say that? If you learn to ask these questions, to see literary texts through these glasses, you will read and understand literature in a new light, and it’ll become more rewarding and fun.

Memory.

Symbol. Pattern. These are the three items that, more than any other, separate the professorial reader from the rest of the crowd. English professors, as a class, are cursed with memory. Whenever I read a new work, I spin the mental Rolodex looking for correspondences and corollaries—where have I seen his face, don’t I know that theme? I can’t not do it, although there are plenty of times when that ability is not something I want to exercise. Thirty minutes into Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider (1985), for instance, I thought, Okay, this is Shane (1953), and from there I didn’t watch another frame of the movie without seeing Alan Ladd’s face. This does not necessarily improve the experience of popular entertainment.

Professors also read, and think, symbolically. Everything is a symbol of something, it seems, until proven otherwise. We ask, p. xvi Is this a metaphor? Is that an analogy? What does the thing over there signify? The kind of mind that works its way through undergraduate and then graduate classes in literature and criticism has a predisposition to see things as existing in themselves while simultaneously also representing something else. Grendel, the monster in the medieval epic Beowulf (eighth century A.D.), is an actual monster, but he can also symbolize (a) the hostility of the universe to human existence (a hostility that medieval Anglo-Saxons would have felt acutely) and (b) a darkness in human nature that only some higher aspect of ourselves (as symbolized by the title hero) can conquer. This predisposition to understand the world in symbolic terms is reinforced, of course, by years of training that encourages and rewards the symbolic imagination.

A related phenomenon in professorial reading is pattern recognition. Most professional students of literature learn to take in the foreground detail while seeing the patterns that the detail reveals. Like the symbolic imagination, this is a function of being able to distance oneself from the story, to look beyond the purely affective level of plot, drama, characters. Experience has proved to them that life and books fall into similar patterns. Nor is this skill exclusive to English professors. Good mechanics, the kind who used to fix cars before computerized diagnostics, use pattern recognition to diagnose engine troubles: if this and this are happening, then check that. Literature is full of patterns, and your reading experience will be much more rewarding when you can step back from the work, even while you’re reading it, and look for those patterns. When small children, very small children, begin to tell you a story, they put in every detail and every word they recall, with no sense that some features are more important than others. As they grow, they begin to display a greater sense of the plots of their stories—what elements actually add to the significance and which do not. So too with readers. Beginning students are often p. xvii swamped with the mass of detail; the chief experience of reading Dr. Zhivago (1957) may be that they can’t keep all the names straight. Wily veterans, on the other hand, will absorb those details, or possibly overlook them, to find the patterns, the routines, the archetypes at work in the background.

Let’s look at an example of how the symbolic mind, the pattern observer, the powerful memory combine to offer a reading of a nonliterary situation. Let’s say that a male subject you are studying exhibits behavior and makes statements that show him to be hostile toward his father but much warmer and more loving toward, even dependent on, his mother. Okay, that’s just one guy, so no big deal. But you see it again in another person. And again. And again. You might start to think this is a pattern of behavior, in which case you would say to yourself, “Now where have I seen this before?” Your memory may dredge up something from experience, not your clinical work but a play you read long ago in your youth about a man who murders his father and marries his mother. Even though the current examples have nothing to do with drama, your symbolic imagination will allow you to connect the earlier instance of this pattern with the real-life examples in front of you at the moment. And your talent for nifty naming will come up with something to call this pattern: the Oedipal complex. As I said, not only English professors use these abilities. Sigmund Freud “reads” his patients the way a literary scholar reads texts, bringing the same sort of imaginative interpretation to understanding his cases that we try to bring to interpreting novels and poems and plays. His identification of the Oedipal complex is one of the great moments in the history of human thought, with as much literary as psychoanalytical significance.

What I hope to do, in the coming pages, is what I do in class: give readers a view of what goes on when professional students of literature do their thing, a broad introduction to the codes and patterns that inform our readings. I want my students not p. xviii only to agree with me that, indeed, Mr. Lindner is an instance of the demonic tempter offering Walter Lee Younger a Faustian bargain; I want them to be able to reach that conclusion without me. I know they can, with practice, patience, and a bit of instruction. And so can you.

How to Read

Literature

Like a

Professor

1 – Every Trip Is a Quest (Except When It’s Not)

p. 1 OKAY, SO HERE’S THE DEAL: let’s say, purely hypothetically, you’re reading a book about an average sixteen-year-old kid in the summer of 1968. The kid—let’s call him Kip—who hopes his acne clears up before he gets drafted, is on his way to the A&P. His bike is a one-speed with a coaster brake and therefore deeply humiliating, and riding it to run an errand for his mother makes it even worse. Along the way he has a couple of disturbing experiences, including a minorly unpleasant encounter with a German shepherd, topped off in the supermarket parking lot where he sees the girl of his dreams, Karen, laughing and horsing around in Tony Vauxhall’s brand-new Barracuda. Now Kip hates Tony already because he has a name like Vauxhall and not like Smith, which Kip thinks is pretty p. 2 lame as a name to follow Kip, and because the ’Cuda is bright green and goes approximately the speed of light, and also because Tony has never had to work a day in his life. So Karen, who is laughing and having a great time, turns and sees Kip, who has recently asked her out, and she keeps laughing. (She could stop laughing and it wouldn’t matter to us, since we’re considering this structurally. In the story we’re inventing here, though, she keeps laughing.) Kip goes on into the store to buy the loaf of Wonder Bread that his mother told him to pick up, and as he reaches for the bread, he decides right then and there to lie about his age to the Marine recruiter even though it means going to Vietnam, because nothing will ever happen for him in this one-horse burg where the only thing that matters is how much money your old man has. Either that or Kip has a vision of St. Abillard (any saint will do, but our imaginary author picked a comparatively obscure one), whose face appears on one of the red, yellow, or blue balloons. For our purposes, the nature of the decision doesn’t matter any more than whether Karen keeps laughing or which color balloon manifests the saint.

What just happened here?

If you were an English professor, and not even a particularly weird English professor, you’d know that you’d just watched a knight have a not very suitable encounter with his nemesis.

In other words, a quest just happened.

But it just looked like a trip to the store for some white bread.

True. But consider the quest. Of what does it consist? A knight, a dangerous road, a Holy Grail (whatever one of those may be), at least one dragon, one evil knight, one princess. Sound about right? That’s a list I can live with: a knight (named Kip), a dangerous road (nasty German shepherds), a Holy Grail (one form of which is a loaf of Wonder Bread), at least one dragon (trust me, a ’68 ’Cuda could definitely breathe p. 3 fire), one evil knight (Tony), one princess (who can either keep laughing or stop).

Seems like a bit of a stretch.

On the surface, sure. But let’s think structurally. The quest consists of five things: (a) a quester, (b) a place to go, (c) a stated reason to go there, (d) challenges and trials en route, and (e) a real reason to go there. Item (a) is easy; a quester is just a person who goes on a quest, whether or not he knows it’s a quest. In fact, usually he doesn’t know. Items (

b) and (c) should be considered together: someone tells our protagonist, our hero, who need not look very heroic, to go somewhere and do something. Go in search of the Holy Grail. Go to the store for bread. Go to Vegas and whack a guy. Tasks of varying nobility, to be sure, but structurally all the same. Go there, do that. Note that I said the stated reason for the quest. That’s because of item (e).

The real reason for a quest never involves the stated reason. In fact, more often than not, the quester fails at the stated task. So why do they go and why do we care? They go because of the stated task, mistakenly believing that it is their real mission. We know, however, that their quest is educational. They don’t know enough about the only subject that really matters: themselves. The real reason for a quest is always self-knowledge. That’s why questers are so often young, inexperienced, immature, sheltered. Forty-five-year-old men either have self-knowledge or they’re never going to get it, while your average sixteen-to-seventeen-year-old kid is likely to have a long way to go in the self-knowledge department.

Let’s look at a real example. When I teach the late-twentieth-century novel, I always begin with the greatest quest novel of the last century: Thomas Pynchon’s Crying of Lot 49 (1965). Beginning readers can find the novel mystifying, irritating, and highly peculiar. True enough, there is a good bit of cartoonish p. 4 strangeness in the novel, which can mask the basic quest structure. On the other hand, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (late fourteenth century) and Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queen (1596), two of the great quest narratives from early English literature, also have what modern readers must consider cartoonish elements. It’s really only a matter of whether we’re talking Classics Illustrated or Zap Comics. So here’s the setup in The Crying of Lot 49:

How to Read Literature Like a Professor

How to Read Literature Like a Professor